by Maria Macapagal

# 2001-039

This paper is property of the Northern Virginia Folklife Archive. Users are required to cite NVFA, paper ID number, and author.

| Works Cited |

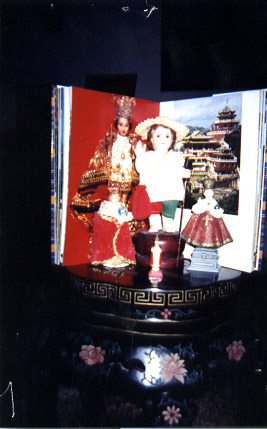

| Figure 1: Altar

of Large Virgin and Various Saints in Family Room |

Within every home there is a specially designated space where members of a household can come together to share a meal, share their day, or share their lives. Whether this space is centered on a table or a television set, it is oftentimes considered to be the beating heart of the home. It is here that the life-blood of a home - its family-gathers to communicate and interact before flowing away to their respective areas. Likewise, in a business, the heart is perhaps the kitchen in a restaurant where the vital products for exchange are stored, produced, and later distributed. Perhaps, to some, the heart of a business is the safe in the backroom or the cash register where profits, the business' means of nourishment, are stored. Although these places are the likeliest to be considered the heart and the vitality of a home or business, to the majority of the Catholic Filipino community, it is the religious altar that brings luck, life, and vitality. In particular, these religious altars illustrate the widespread devotion to the Santo Nino and the Blessed Virgin Mary. In order to understand the intricacies of Filipino religious devotion, it is important to venture back to the islands and briefly recall the origins of Filipino Catholicism and how it has assimilated with indigenous spiritual beliefs and practices. Prior to the Spanish colonialism, the Philippines practiced polytheistic Shamanism. These beliefs consisted of an intense spiritual connection to nature and included sacrifices and incantations to spirits of the sky, earth, dwelling places and gardens (Dolan 99). Ancestors were also included among the assembly of deities, which seems to be an influence of early Chinese trade and migrations around the tenth century C.E (Roces 136). Since these various spirits could be passive, aggressive, benevolent, or malevolent, a Shaman was often employed to communicate and thereby pacify the spirits on behalf of the community (Dolan 99). After Spanish colonization and the advent of Catholicism, however, it seems that this communication and interaction with the spirit world was displaced onto the various key figures of Christianity, namely the saints, the Virgin Mary, and the Santo Nino, or Infant Jesus. According to the ethnographer Raul Pertierra, "Christian notions of God, salvation, and sin have been adapted to fit preexisting religious expectations...The relationship with saints is based on an exchange of services...The saint obtains regular worship for which he or she dispenses a favor, similar to the relationship with ancestral and environmental spirits"(Pertierra 140-141).

The veneration to the statue of the Virgin Mary began during Miguel Lopez

de Legazpi's conversion movement of the sixteenth century C.E. (Roces

142). It was after his fleet captured Manila that he came upon a wooden

statue of a beautiful woman among the spoils of their conquest. Although

there was no official record stating that this was in fact an image of

the Virgin Mary, Legazpi, nonetheless, declared it miraculous and enshrined

it within Manila's Ermita Church where it remains today (Roces 143). The

Santo Nino, like the image of His mother, enjoys widespread popularity

within the Filipino communities both in the Philippines and here in the

United States.

| Figure 2: Various Santo

Ninos |

The Santo Nino Statue has European origins and is sometimes called Santo Nino de Praga or the Infant of Prague (Pertierra 67). According to the legend in Prague, the Holy Infant is said to have requested that He be dressed in royal robes and displayed publicly for veneration. In fact His exact words were something to the effect of " The more you honor Me, the more I will bless you" (Dominican Fathers Pamphlet). This system of reciprocity is, no doubt, the motivation behind the almost cult-like veneration of the Santo Nino. The components of veneration even border on the bizarre during the Ati-atihan Festival of Kalibo, which is in honor of the image. During this fiesta, the image is threatened with immersion if it does not comply with the requests of the community to bring a much-needed rainfall (Roces 143).

In the United

States the images of the Virgin and the Santo Nino are both integral parts

of the spiritual and daily lives of Filipinos. Growing up, my mother always

emphasized the importance of these figures as if they were actual members

of the family. During our interview, I, again, posed the question "Why

is it so important to have these statues if our faith should reinforce

the fact that God is everywhere and not just contained within an image?"

My mother's reply

and the irritation she exhibited at me even asking such a ridiculous question

was, " If it weren't for them [Santo Nino and the Virgin] we would

not have money, a house, anything, don't you know that? That's why you

have to be good to them so they will bless us." I found this to be

just the response I expected. When I asked my mother if she knew that

the indigenous religious practices of the Philippines involved shamanism,

she promptly denied that it was true. She said, "Aaayyy! Stop that!

The Philippines is Catholic!" I thought to myself, why is she being

so defensive? I am certainly not accusing her of polytheistic practices.

Then I thought that perhaps her protestations stem from her subconscious

realization that, yes, maybe her rituals and beliefs are somehow connected

to this "primitive" practice of spirit worship. In addition,

to a Christian, idolatry is a serious sin condemned by the Ten Commandments

and who would want to offend God in such a way? Despite my mother's denials,

however, as far away as twenty-first century United States, there seems

to be a definite correlation between the remnants of an intrinsic indigenous

spirituality and the Catholicism that "replaced" it during the

Spanish occupation. It is this devotion and system of reciprocity that

motivates the assembling of altars within the home and in businesses.

Since as far

back as I can remember, my mother, a devout Catholic Filipino, has assembled

altars in various places in our home. One of these altars is her private

altar that is situated atop her dresser in such a way that it assumes

an almost protective function as she and my father sleep. This altar is

composed of dozens of prayer cards to various saints that she has either

collected from funeral homes or picked up at church. When I asked her

whether she actually read from these cards she responded, " No, they

are just there so the saints know I am thinking of them." These cards

are, in a sense, "implied prayers" that do not need a voice

because the presence of the words is enough. Beside these prayer cards,

stands her ten inch tall Santo Nino. This image of the Christ Child is

dressed in native Filipino dress unlike the traditional versions that

are attired in elaborate robes and crowns and resemble infant kings. This

particular Santo Nino is wearing a straw hat, a thinly woven sleeveless

shirt and knee length pants. His red shoulder sack, doe-eyed expression,

and exquisite eyelashes give Him the appearance of a young barrio boy

off to market. At the other end of her altar is yet another Santo Nino,

a rather old and weathered one that I remember from my earliest childhood.

This Santo Nino is made of painted ceramic that has become chipped with

age and my playful curiosity. I remember well the scolding I received

for accidentally breaking off His head back when I thought that He was

a pretty doll. My mother neither starts nor ends her day before sitting

on the edge of her bed towards her altar with her requests and gratitude.

Unlike many mothers

who pride themselves on prize roses or tulip beds, my mother is constantly

adding to or rearranging the "main altar" which is on a table

set up against the wall in our family room. Amidst vases of dried or forgotten

bouquets, an artificial floral arrangement, and stumps of wax that were

once candles, stands a tall statue of the Virgin Mary. She towers over

various other statuettes of saints and Santo Ninos all still in their

original plastic coverings. Here, during special occasions or to implore

blessings, our family kneels upon the hard wood floor to say the Rosary

together. It is also at this altar that my mother's confounding sense

of devotion is regularly displayed. When my brother disrupts prayers or

if any of us fail to respond on cue, my mother immediately stops mid-prayer

and does not continue until we have sufficiently apologized to the Virgin's

statue for our irreverence. When we are leaving on a trip or if we need

luck, my mother strokes the Virgin's head and asks for blessings in her

most imploring voice. I have often asked her why she assumes that the

Virgin Mary would want her head stroked and, again, she looks at me as

if I were speaking a great heresy. This is why I decided to include this

question in the interview. I could ask her under the guise of scholarly

research. Her response, although still defensive, was quite interesting.

She responded, " Because, it's to show I love her so she will hear

the prayer."

" But why

do you need to pat her on the head? I'm sure she can hear you without

you having to do that." I asked.

" Stop asking,

you'll make her mad. You should be more loving, and then maybe you will

have more blessings. Mama Mary will answer your prayers!" She replied.

That was the point at which I decided to refrain from continuing this

particular line of questioning. Her responses also seem to be in defense

of a tradition that belongs to our culture, and I, having been born and

raised in the United States, may appear perhaps condescending or ignorant

of my own origins in her eyes when I question her religious practices.

Although that is far from my intention, my mother may believe that these

practices in our family will end with her generation and that future generations

will no doubt be more and more Americanized. Ritual will be replaced with

self-determination, Divine Intersession with the Internet.

There is yet another altar in my house and it belongs to my grandparents, my aunt, and my cousin who live in the apartment that used to be our basement. Their altar is placed above the thirty-two inch television set and cable box. This juxtaposition of tradition and entertainment places the altar in the center of attention at all times. When the television is on, it is impossible to ignore the nearly two-foot statue of Our Lady of Fatima on her cable box pedestal or the elaborately dressed Santo Nino I gave my grandmother years ago when she was quite sick in the hospital. When I told my aunt that I thought that it was interesting that they placed their altar on top of the T.V, she replied, " Oh, because we have nowhere else to put it. But yeah, it's good there so we are always reminded that God is there, everywhere. Even if we are only watching the T.V He is watching us still."

|

| Figure 3: Altar Over TV,

VCR, and Cable Box |

The Santo Nino that I gave my grandmother is special to me because I believe

that He miraculously brought her back from a terrible and serious illness.

He stands on a carved wooden pedestal and is clothed in a red velvet cloak

with gold trim. His hair falls below His shoulders in a mass of brown

ringlets and His angelic face bears just the faintest smile. The golden

crown on His brow declares Him the Great King of the World who heeds the

call of His lowly subjects and to whom I am deeply grateful.

Altars are not only found in Filipino homes but also in Filipino owned businesses. During this phase of my fieldwork, extracting information from the various proprietors of these businesses was a challenge. The two typical reactions I received were either out of shyness or pride. The first business I went to was the Fiesta grocery store in Arlington, Virginia. Here, the altar was situated in the right hand corner behind the counter. It contained the quintessential Santo Ninos and Virgins along with the propped up prayer cards depicting various saints and prayers. Unfortunately, the woman behind the counter simply declined my request to be interviewed claiming that she was too bashful. She did remark that the altar was "just part of our tradition, that's it." Although I was disappointed by my fruitless first attempts at fieldwork, I decided to try again at the Filipino restaurant two doors down called Little Quiapo where my mother was patiently waiting for me to return so that we could order our lunch. In the Little Quiapo, the altar is located high above the counter on top of a small shelf. This altar consists of a central Sacred Heart Jesus figure flanked on one side by a Santo Nino and on the other a statue of Our Lady of Fatima. Interestingly, this altar was well lit by the light of two electric candles on either side. These candles reminded me of the altar in a Chinese restaurant that my family likes to frequent on Sundays.

The only difference

was that the candles in the Chinese restaurant were red and surrounded

what looked like a Daoist Immortal. When I asked Violi, the owner, what

the significance of the altar was in relation to her restaurant she was

more than willing to reply. She responded, " Why we have that?...That's

uh.. that's uh... our patron. That's our patron and we believe in God...um,

you know of course we're Catholic, one hundred percent Catholic... You

know that Mama Mary? She came from Rome. My sister went to Rome and brought

her [statue] here. When my sister went to the Philippines, she gave us

the Santo Nino. Every time, they say, that someone gives you that, it's

good luck. I always pray to Mama Mary, you know, if you have problems,

you know. For the business, for the kids, you know, before I had a problem

child...And besides, you know, it's good luck and you need to pray, you

need to pray." Like my mother, Violi is adamant about her Catholicism.

She repeats this fact twice during our interview. She says, "...we're

Catholic, one hundred percent Catholic." Although I am merely speculating

about her motivations behind this repetition, it seems that she does not

want observers, like myself, to equate her faith with the Daoist or the

Buddhist. To a righteous Catholic, Immortals and Buddhas are only idols,

and certainly to Violi, Christ and the Virgin are definitely not idols.

Another restaurant

that has an altar behind the counter is Fiesta sa Nayon, a popular Filipino

eatery in Orlando, Florida. Their altar is composed of three relatively

large Santo Ninos. These Santo Ninos are dressed in the traditional kingly

attire and watch protectively from the high shelf upon which they stand.

Although I was unable to interview the proprietors of this restaurant,

their altar seems to take on a similar role to that in Little Quiapo.

These altars serve the function of protectors, benefactors, and bringers

of luck.

After I finished the process of collecting my information, I realized that fieldwork is not an easy task to undertake. The informants I found who were willing to participate and be quoted were few and the disappointment of rejection can be quite discouraging. Also, informants may find your research to be trivial when it pertains to the beliefs that they have held to be unquestionable for their entire lives. "Why are you asking about this?" was the initial question I encountered during each attempt. Even after explaining to them the purposes for my research, they still looked at me as though I were asking why water is wet. Despite these drawbacks, however, I was able to gather some important information regarding the basic functions of the Filipino home and business altar. In both places, the figures of the altar serve as protectors. Within the home, an altar can ward against intruders, evil spirits, and familial discord. In a business, the altar can guard against robbers, again, evil spirits, and disruptive customers. They are also there to insure good fortune. The functions of the altars in both environments differ in terms of personal devotion. Aside from protecting our home, my mother believes that acting and speaking lovingly to her various statues will ensure a response to her requests and prayers. The reassurance of a profitable business and many loyal customers is the reason many business owners may pray to their altars. To display an altar before the public the way Violi does seems to be an attempt to openly acknowledge her faith and thereby gain merit for herself and her business. The motivation behind these altars may be tailored to suit different purposes depending on whether they are in homes or in restaurants. I have found the underlying inspiration, however, is a profound faith in God and in the daily communication that runs steadily between heaven and earth.

Bes, Aloma (aunt).

Interview. 18 Apr. 2001.

Dolan, Ronald, ed. Philippines, a Country Study. Library of Congress:

Washington, D.C. 1993.

Dominican Fathers. Shrine of the Infant of Prague. Brief History of the

Devotion to

Infant of Prague: Connecticut

Macapagal, Web (mother). Interview. 15 Apr. 2001.

Pertierra, Raul. Religion, Politics, and Nationality in a Philippine Community.

University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu. 1988.

Roces, Alfredo and Grace. Culture Shock: A Guide to Customs and Etiquette-

Philippines

Graphic Arts Center: Portland. 1994.

.Violi. Interview. 20 Apr. 2001.

Web Macapagal : April 15, 2001 MM: We've had altars to the Virgin Mary,

to Jesus, and the saints since as far back as I remember. Why are these

altars such as important part of our home?

WM: Because that is what we believe. Why? You know we need to pray, so

we need the altars. They are for protection and for blessing the house.

MM: Why is it so important to have these statues if our faith should reinforce

the fact that God is everywhere and not just contained within an image?

WM: If it weren't for them we would not have money, a house, anything,

don't you know that? That's why you have to be good to them so they will

bless us.

MM: What about the altar in your room? Do you pray all those prayers on

the cards?

WM: No, they are just there so the saints know I am thinking of them.

MM: Did you know that the earliest natives in the Philippines, before

the Chinese and the Spanish, practiced polytheism and shamanism? They

worshipped nature and spirits. Do you think that that original practice

is still seen in how we pray today?

WM: Aaayyy! Stop that! The Philippines is Catholic.

MM: I'm not saying they still offer sacrifices or anything, or that we

believe in other gods but it is historically true. We only became Catholic

after the Spanish came in the 16th century.

WM: The Philippines is Catholic. We pray the Rosary. Who cares about the

natives? The Virgin Mary is the patron of the Philippines. And yes, in

some provinces they believe in spirits like the aswang but our religion

is Catholic. Just because some people believe in ghosts does not mean

that they believe... that they pray to them.

MM: We'll, I'm just saying that usually in order for a new religion to

become accepted it must become accessible to the indigenous people. It

has to be easy for them to understand. Anyway, I also notice, and I've

mentioned this before, that you talk to the statues and pat the Virgin's

head. Why do you do that?

WM: Because, it's to show I love her, so she will hear the prayer.

MM: But why do you need to pat her on the head? I'm sure she can hear

you without you having to do that.

WM: Stop asking! You'll make her mad. You should be more loving and then

maybe you will have more blessings. Mama Mary will answer your prayers.

What else do you need to ask?

MM: I guess you answered all my questions. Thank you for letting me interview

you.

WM: I don't see why you are researching faith. You know all this.

Transcript #2

Aloma Bes: Interview.

April 18, 2001 MM: Hi! are you busy? I just have a couple questions to

ask you about the statues on top of the T.V.

AB: Why? What do you need to know?

MM: Well I'm doing research about religious altars in houses and businesses

and I thought that it was interesting that you put yours on top of the

T.V.

AB: (laughing) Oh, because we have nowhere else to put it. But yeah, it's

good there so we are always reminded that God is there, everywhere. Even

if we are only watching T.V. He is watching us still.

MM: That's pretty cool. You know, that you didn't really plan it but it

just sort of works out like that.

AB: Yeah, maybe God wanted it that way. That's why we have no space here

(laughing)

MM: The altar is also for blessings and luck too right?

AB: Yeah, yeah. It watches over us, your lola and lolo.

MM: Okay, thanks for answering my questions.

AB: Sure. Anytime.

Transcript #3

Violi Interview. April 20, 2001 MM: I know you're busy but can you answer

a few questions about the altar you have up there? I'm writing a paper

for my folklore class about altars in homes and businesses.

V: Sure. Why altars? Isn't that religion not folklore.

MM: Well, my paper kind of has to do with the rituals and beliefs behind

the altar, for example, is your altar important to the restaurant? Why

do you have it?

V: Why we have that?...That's uh...that's uh...our patron. That's our

patron and we believe in God...um...you know of course we're Catholic,

one hundred percent Catholic. You know that Mama Mary? She came from Rome.

My sister went to Rome and brought her here. When my sister went to the

Philippines, she gave us the Santo Nino. Every time, they say, that someone

gives you that, it's good luck. I always pray to Mama Mary, you know,

if you have problems you know. For the business, for the kids, you know,

before I had a problem child...And besides, you know, it's good luck and

you need to pray, you need to pray.

MM: So it's kind of like when Chinese restaurants have Buddhas? For prosperity

and luck?

V: Not really, I pray to them sometimes, when I'm not busy, when I'm busy,

you know. It's not like Buddha because, you know, Buddha is for good luck,

you know. I have a Buddha over there for decoration but not for praying.

MM: Okay, I know you have customers but I appreciate the time you took

to let me interview you.

V: No problem, did you like the food?......

The Ati-atihan Fiesta for the Santo Nino de Praga

The Ati atihan

Festival honoring the Santo Nino is a joyful celebration during which

the Santo Nino statue is processed throughout the town and given offerings.

This festival is rooted in pre-Hispanic folk tradition that commemorates

the peace offering given by the indigenous tribe, the Ati, to the Malay

immigrants. Today the festival exemplifies the assimilation of Catholic

rituals and beliefs with indigenous folk traditions.

During the festival the community participates with exuberant merry-making.

Most paint their bodies with soot, put leaves in their hair, and dance

in the streets carrying poles topped with various offerings of food. Often,

live birds are tied to the ends of the pole as well. While dancing, wild

shouts of praise go out to the Santo Nino and chants of "viva Santo

Nino!" resonate throughout the town.

It is also during this festival that special petitions for rain are made

to the statue. Oddly, the Santo Nino is then threatened with immersion

if he fails to comply.